By Jim Beal Jr.

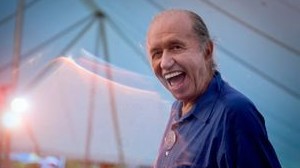

It’s not easy to find a photograph or a video clip in which Bob Dorough is not smiling.

Singer, songwriter, pianist, arranger, etc. Dorough, 89, has reason to smile. During a career that started in Texas, at Plainview High School, Dorough has played piano behind Sugar Ray Robinson when Robinson was tap dancing, not boxing; sung with Miles Davis; backed Blossom Dearie at the Mars Club in Paris; penned standards such as “Devil May Care;” arranged songs for The Fugs; produced albums for the band Spanky and Our Gang and turned a couple of generations on to the joy of multiplying via “Schoolhouse Rock” songs such as “Three Is a Magic Number.” Dorough might well be the happiest man in jazz.

Singer, songwriter, pianist, arranger, etc. Dorough, 89, has reason to smile. During a career that started in Texas, at Plainview High School, Dorough has played piano behind Sugar Ray Robinson when Robinson was tap dancing, not boxing; sung with Miles Davis; backed Blossom Dearie at the Mars Club in Paris; penned standards such as “Devil May Care;” arranged songs for The Fugs; produced albums for the band Spanky and Our Gang and turned a couple of generations on to the joy of multiplying via “Schoolhouse Rock” songs such as “Three Is a Magic Number.” Dorough might well be the happiest man in jazz.

“I’m a fun guy,” Dorough said via telephone from his home in Pennsylvania. “I don’t take myself too seriously. The argument has been made that I’m not a jazz guy, I’m an entertainer.

“My voice wasn’t really that great when I moved to New York. I went to the union hall and if they said they needed a singing piano player, I was there. I worked in a lot of bars where I’d sing Hoagy Carmichael songs and Nat King Cole songs and hoped people would listen.”

It’s a safe bet people will listen to Dorough on Thursday evening during a concert in Northwest Vista College’s Palmetto Center for the Arts. He’ll be joined by Northwest Vista professor/jazz vocalist Katchie Cartwright and Cartwright’s husband, sax man Richard Oppenheim.

Dorough has a wide range of musical interests. He cultivated that range in an Army band during World War II; at North Texas State University (now the University of North Texas), where he earned a bachelor of music degree in 1949; and while working in Los Angeles and New York City.

He started recording as a leader in the mid-’50s with the “Devil May Care” album and has released a string of discs including “Too Much Coffee Man” on Blue Note. His latest CD, “The Houston Branch,” features Dorough working with his daughter, Houston Symphony flutist Aralee, and her husband, oboe player Colin Gatwood.

“Maybe they’re just weird happenings,” he said, laughing. “A lot of things I’ve done I’ve done because I needed a gig. I was always messing with a piano. I used it as a way to study harmonies because they’re all there in the black and white keys.

“I majored in composition, but I fell in love with jazz. I was interested in jazz, classical, blues, folk and even a little rock ‘n’ roll. I’ve kept an open, eclectic mind, so I have a very wide knowledge of music from Stravinsky to Mick Jagger. Songwriting is a talent and a craft and an individual approach to music.”

Dorough has been described as a master of vocalese, putting lyrics and scat singing to instrumental jazz.

“I don’t agree with vocalese as a term. I see it as vocalizing jazz. But I don’t fight it anymore,” Dorough said. “Annie Ross’s ‘Moody’s Mood for Love’ really knocked me out. Eddie Jefferson was the greatest and Jon Hendricks surpassed them all.

“I tried a few. Charlie Parker’s ‘Yardbird Suite’ was my first one and I sang Charlie Parker’s solo as best I could. I sang from childhood. I sang along with the radio. There weren’t as many influences then as there are now, but great instrumentalists like Trummy Young, Jack Teagarden and Nat Cole also sang.”

In the ’60s, when rock began taking up a whole lot of musical space, Dorough found gigs hard to come by. He and bassist Ben Tucker started an advertising business doing jingles. The Dorough/Tucker team also penned “Comin’ Home Baby,” a hit for Mel Tormé.

Through that partnership came “Schoolhouse Rock,” a project that started as an idea for an album and grew to become a popular ABC TV show from 1973-1985 and had another run in the ’90s.

“They wanted a song about multiplication and I had a pretty good grasp of numbers,” Dorough said, laughing again. “I became the music director, but I didn’t write all the songs. Dave Frishberg came onboard, and so did Lynn Ahrens, a wonderful writer who’s now on Broadway.”

Dorough offered his advice to songwriters and to musicians.

“As far as singers and songwriters, study music,” he said. “For musicians, it’s a tougher market now than it ever has been. You’ve got to learn everything you can. You’ve got to learn music history and variety. You’ve gotta study music.”